December 5, 2016

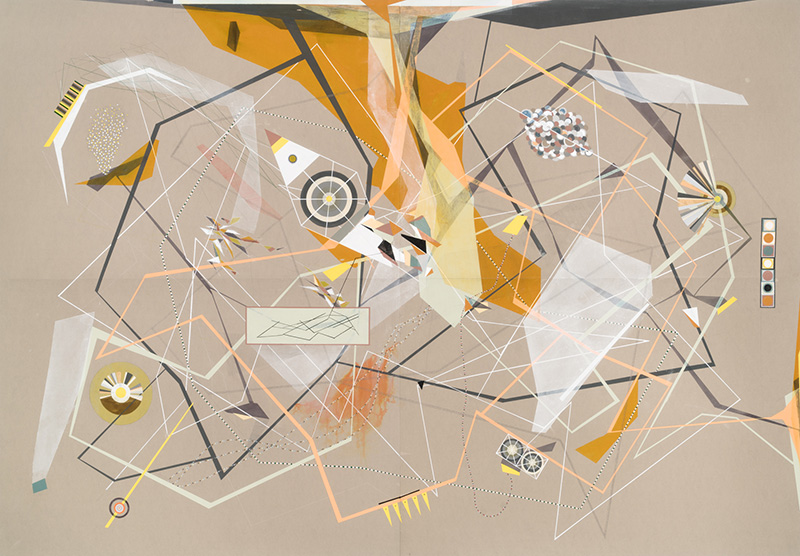

Linear Momentum and Collisions, 2016, gouache, ink, colored pencil, graphite and pastel on paper, 55 x 79"

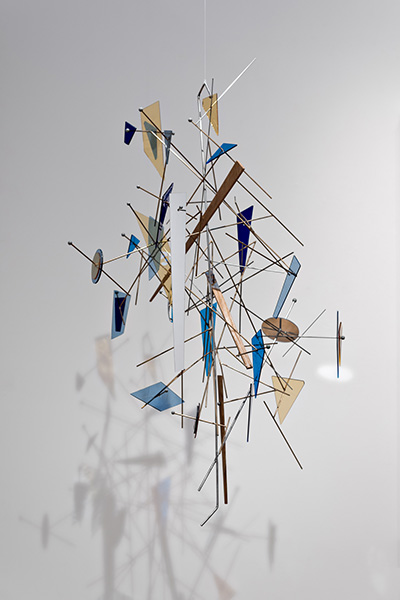

Blue Constellation (detail), 2016, copper, stainless steel, stained glass and ceramic 39 x 24 x 24"

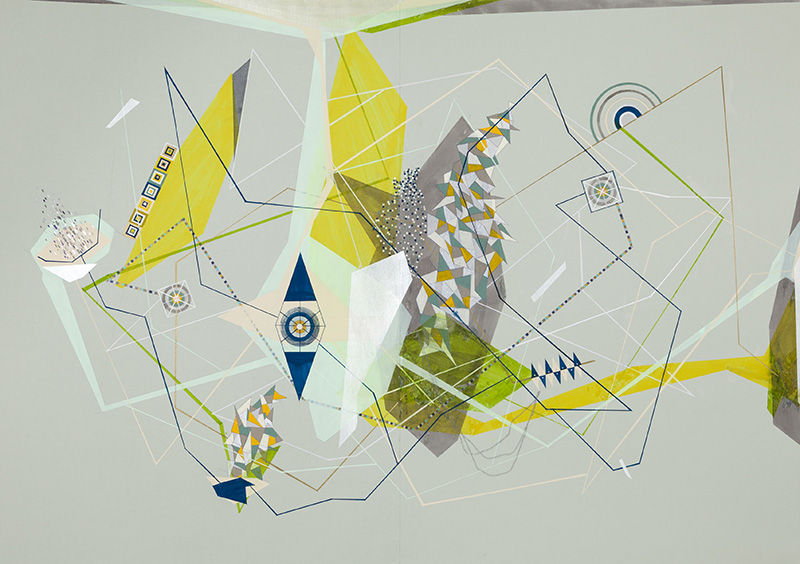

Escapement Mechanism, Cross Sections of Permeability and Lightness, 2016, acrylic on canvas 72 x 60"

Clevegan: City System with Invisible Diagram Line Possibility and Hollow Green Grey Velocity Transmitter, 2014-2015, pencil, ink, gouache, acrylic on Fabriano Murillo Paper 39 1⁄2 x 55"

Dannielle Tegeder @ Gregory Lind

by David M. Roth

In repurposing ideas of the Russian avant-garde, New York artist Dannielle Tegeder proves yet again just how persistently relevant early Modernism is. While architecture and graphic design continue to be its main beneficiaries, the last 15 or so years have seen a noticeable uptick in the number of artists who’ve adopted the outward trappings of Constructivism and Suprematism: their sharp angles, pencil-thin lines, empty volumes, floating orbs, intersecting planes and schematic/diagrammatic structure. Today, these visual tropes are being subsumed into a sub-genre within abstract painting, dominated by references to mapping, biology and geography and to networked systems, particularly those involving communication and transportation and heavy industry.

Leaders of this micro-trend, in addition to Tegeder, include Julie Mehetru, Matthew Ritchie, Kristin Baker and Alex Couwenberg. Unlike their forbearers who split along ideological lines — dividing between those dedicated to political goals and those devoted to spiritual pursuits — these Neo-Constructivists align with no particular faction. Their oscillations, between the concrete allusions generated by representation and the more nebulous associations triggered by age-old mystical symbols, are their strength. That the results seem tailor-made for our own historical moment comes as no surprise given the historical record of utopias turning into their opposites.

Tegeder's spooky, geometry-laced paintings, drawings and sculptures don’t describe dystopia, but they certainly hint at it. Her works consist of dots, circles, lines, vertices, accordion shapes and color swatches laid onto drab-colored grounds, hues of which evoke the kind of unease you feel at military bases and prisons. Other elements counteract that feeling. Blue Constellation, a ceiling-hung sculpture composed of metal rods interlaced with translucent glass disks, does so by bringing to mind a game that, beginning in the 1930s, introduced kids to the pleasures of geometry (and by extension geometric abstraction). It was called Pick-up Sticks. I have no idea if Tegeder played it, but almost all of her work contains overlapping and intersecting stick-like elements. They evince and encourage a high-level of playfulness that infuses everything she does, from the eight small-to medium-sized drawings and canvases on view here to the stunning wall paintings and sculptural installations that figured so prominently in the artist’s 2013 survey (Painting in the Extended Field) at the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art in Clinton, New York.

Tegeder grew up in a family of steamfitters, the tradespeople who outfit buildings with plumbing and piping. Before taking up art she planned to join their ranks, and that experience, of having schematic drawings dissected at the dinner table, was formative. Absent that knowledge, you might just as easily see her work being connected to aerial photography. Josh Begley’s satellite photos of prisons and military compounds spring immediately to mind for how strikingly similar they are to what Tegeder does. Deeper still are the connections she pulls from the lesser-known corners of Suprematism’s history, the parts having to do with language and sound. Her last show in this room, The Library of Abstract Sound, featured 86 drawings that were scanned into a computer algorithm to produce music. (The idea is said to have originated with Malevich and his experience with synesthesia.) As for language, Tegeder assigns paragraph-length titles to many of her works. Clevegan: City System with Invisible Diagram Line Possibility and Hollow Green Grey Velocity Transmitter: Forecasting Machine with Suspended City and Ice Habitats with Fire Networks; Miniature Thermal Elements with Utopian Underground Segments with Safety Routes in Snow Green with Developments Contraption and Triangle Headquarters and Complete Love Algorithm and Magnetic Diagram for Beauty is but one example. These she creates from scraps of paper stored in a jar, a method akin to William Burroughs’ cut-ups, and with similar sci-fi/apocalyptic results.

Ultimately, it’s the slippery, non-hierarchical character of her work that I find most appealing. The 2-D works, like the installations, feel as if they are part of some larger entity that extends far beyond anything a single picture or group of pictures can convey. Take, for example, Escapement Mechanism, Cross Sections of Permeability and Lightness and Linear Momentum and Collisions, two works on paper with imposing forms at the edges. Each is severely cropped, as if meant to continue the view someplace else. Like the electronic alliances that arise and dissolve on social media, Teeter’s compositions appear to be provisional without being haphazard; they fan out sharply in all directions in apparent response to unseen stimuli. While we can see in them, analogs to flight patterns, highways and telecommunications networks — or to remote bunkers monitored by electronic eyes and/or TV screens — the stronger sense is of forces or things that cannot really be readily mapped.

That is why, I’m guessing, she calls this show The Geometry of Artificial Life. In a “post-fact” world, where nothing is real and everything is permitted, that designation feels about right.