December 29, 2015

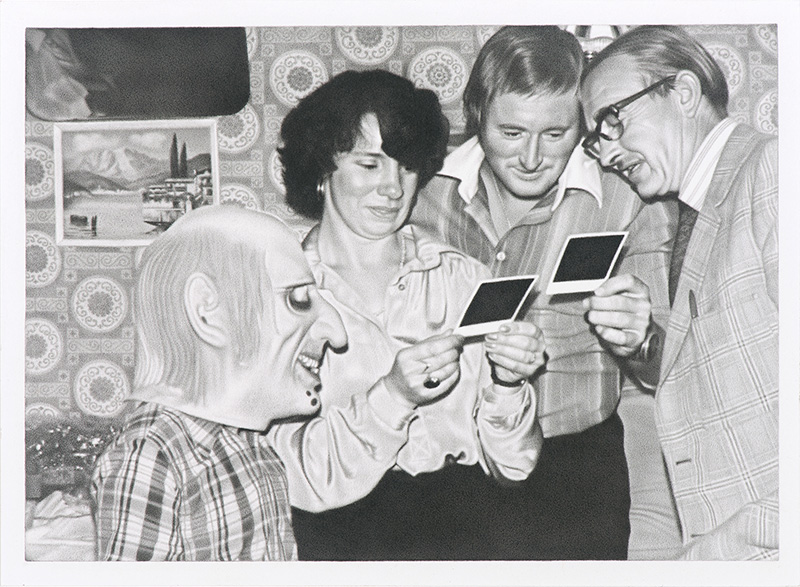

“Little Monsters” (2015),

graphite and pencil on paper

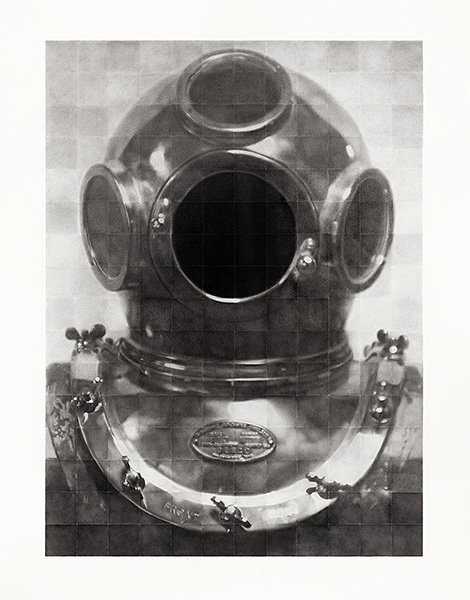

“Big Helmet” (2015),

charcoal on paper

Drawings have therapeutic and artistic intent

By Jessica Zack

The extraordinary degree of photorealistic detail in Ed Loftus’ drawings practically begs viewers to lean in within touching distance of the paper, in disbelief that these small graphite creations are meticulously rendered drawings and not black-and-white photographs.

“It generally makes me happy when that happens because reproducing a photo as exactly as possible is definitely what I was hoping for,” says Loftus, a self-taught, 42-year-old Oakland artist whose latest series of drawings is on view in the new exhibition “Ed Loftus: No One and Nowhere” at the Gregory Lind Gallery.

Technique, however, doesn’t fully explain the emotional power and disquieting nostalgic pull of Loftus’ drawings. Working from old family snapshots and portraits, borrowed imagery and his own recent photos, Loftus creates unusual collages. He then painstakingly replicates them, creating a series of what he calls “reimagined memories.”

“I wanted this show to be more of a concept; all the pieces working together,” he says.

Inspired by the fastidious pencil work of British artist Paul Noble and Latvian Photorealism pioneer Vija Celmins, Loftus creates hyperrealistic works with elements of the surreal.

A recurring antique metal diving helmet appears in one drawing (“Come Up at Once, We’re Sinking,” 2013) on the head of Loftus’ father, who is sunbathing in a 1970s swimsuit. In “Legacy Patterns and Hand-Me-Downs,” a nostalgic vintage snapshot of a family gathered around a television is disrupted by an oversize sunbathing man outside the window.

“Loftus’s work is about emotional dislocation, about belonging and not belonging. … It is about psychological straddling,” writes novelist Rabih Alameddine in the exhibition’s catalog essay.

Loftus, who grew up in Dorset, England, and moved to San Francisco at age 18 to take a shot at professional skateboarding, speaks openly about his lifelong struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He discovered in his 20s that drawing in this photorealistic style helped quell his repetitive thoughts and obsessional thought patterns.

“It is strangely comforting, satisfying, to spend as much time with these images as I do,” says Loftus, who draws with a “regular, very sharp pencil” (working from top left to bottom right, to avoid smudges) in his home studio, listening to 1970s rock and public radio, for at least seven hours every day.

Each of the 11 new drawings in the solo exhibition took between three and six months to complete, explaining the three-year interval since his last solo show. For Loftus, it’s a slow, yet aesthetically and psychologically fulfilling process.

“I don’t know if drawing is therapeutic, but I’m definitely agitated if I haven’t done it in a couple days,” he says.