June 2017

The Case for Tom Burckhardt

He resists institutional notions of what an abstract painting can be.

The day after I visited Tom Burckhardt to see his recent paintings and to hear more about “STUDIO FLOOD,” the installation he is preparing for his upcoming show at Pierogi ( opening September 10, 2017), he sent me an email. It contained a quote from the recently published The Inkblots: Herman Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and the Power of Seeing (2017) by Damion Searls. While I think this quote is a good place to start reflecting on what Burckhardt is up to in his abstract paintings, I first want to establish a context for it.

During my visit, Tom and I talked about Rorschach, inkblots, and symmetry. We briefly touched on works by Andy Warhol, Kerry James Marshall, Bruce Conner, and Jasper Johns. Both Warhol and Marshall appropriated Rorschach’s inkblots, while Conner devised a method that consisted of drawing wet ink lines on one half of a sheet of paper and then folding it down a pre-made crease to leave a mirror image on the other side – an act that slowed down and compartmentalized drawing. Conner’s spidery, symmetrical, linear forms suggest insects and ancient signs. Control and accident mirror each other. In Johns’s paintings and prints titled “Corpse and Mirror,” some of which are sectioned into six rectangles, one rectangle imperfectly mirrors the one adjacent to it, establishing a series of visual echoes.

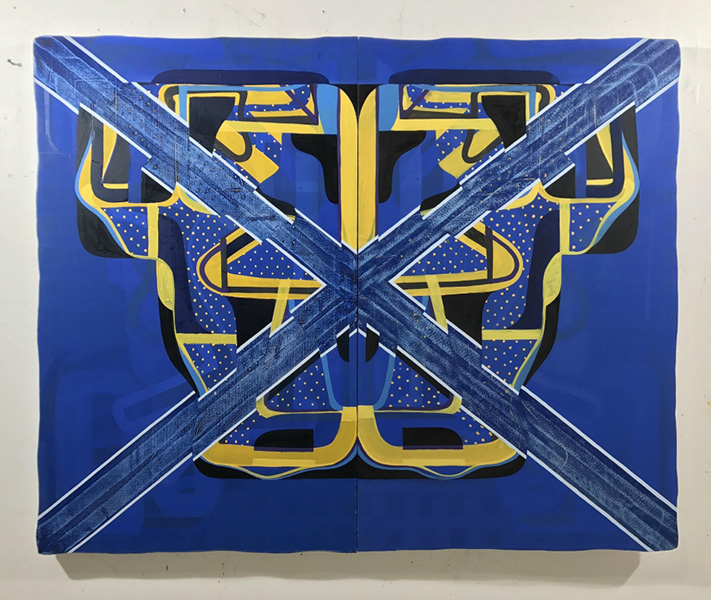

One reason Rorschach’s inkblots came up in the conversation was because all of Burckhardt’s recent paintings are abstract and many are symmetrical. In fact, imperfection is built into the process because Burckhardt always starts with a single panel, with the blank one set aside until the first is completed. An improvisational artist, he works in oil on the panel, sometimes using a roller to cover an area yet allowing the under-layer to peek through, until he arrives at something he considers finished. This and everything else in the first panel has to be redone in reverse on the second panel.

By working on two panels at different times, and then abutting the so-called original and its mirrored copy together, Burckhardt calls attention to the paradox of a symmetrical image that is physically split down the middle: it is at once total and divided.

It does not take long, however, to begin noticing slight differences between the panels in hue and thickness of line. Given the symmetry and the physical split, I found myself asking whether I was seeing more than what was there. This ever so slight push-pull between each panel introduces a tremulous hum into the experience: I begin focusing back and forth between the total image and the two panels, never settling down in either perceptual mode for very long. The dance between similarity and difference doesn’t end. Complicating this experience is the way the figure and ground are often entangled, especially when there is layer of overpainting. I am left wondering, what is the relationship between the dominant form and the partially hidden one?

However, before discussing Burckhardt’s abstract paintings further, I want to circle back to the quote he sent me. One of the people that Searls writes about is the German philosopher Robert Vischer, who coined the word “einfuhling,” which means “feeling in” or, in English, empathy. According to Searls, “Empathy, for Vischer, was creative seeing, reshaping the world so as to find ourselves reflected in it.” Vischer’s “creative seeing” links up with Burckhardt’s longtime interest in pareidolia, or the way the imagination creates patterns, so that you see something you know (face, bat, or gondola) in abstract images.

Burckhardt’s abstract paintings form one distinct body of work within his diverse oeuvre. In addition, he has done installations and made a series of works painted on vintage book covers. I have seen travel journals full of portraits of people he encountered while bicycling in Indonesia. He has made ink-on-paper views of a variety of landscapes and seascapes – often including the motif of a blank stretched canvas — that incorporated digital images. Burckhardt works across these mediums without trying to fit them all together, but, despite all the differences, in each of them he is meditating on the nature of art.

“STUDIO FLOOD” continues a line of thought the he first explored in “FULL STOP” (2005-2006), which is his walk-in version of an artist’s cluttered studio, complete with a doorway entering from a graffiti-covered storefront façade. Everything in this three-dimensional trompe l’oeil environment is made from brown cardboard, hot glue, and flat black paint.

In “STUDIO FLOOD,” the artist’s studio will also be made of cardboard but this time it will supposedly be partially full of water, with the corners and tops of paintings sticking up like shark fins. Disaster has struck, and we must deal with the aftermath. In this scenario, as we enter the studio, we would have to walk on the surface of the water, which is not the metaphor the artist wanted. Instead – as the model he shows me makes clear – the studio will be constructed upside-down, and we will walk on the ceiling: the ground has been pulled out from under us.

Pareidolia is a phenomenon the Rorschach inkblot test makes use of. This is what Tom said in an interview we did in 2011:

The whole idea of pareidolia is that it’s an evolutionary thing that we had to develop to instantly recognize friend or foe, it’s a subcortical kind of image, it’s the primary kind of image processing that we have had as a species, and I want to tap into its hook, as in a pop song hook, and to make use of that. If I were a really good abstract painter, as soon as that face starts appearing, I’d want to turn the canvas and run in the other direction. I’m perversely trying to cultivate the thread that comes out of pareidolia, the creation of images, a facial image out of a random stimulus, basically, because random stimulus is the basis of abstract painting, right?

Pareidolia is what Robert Vischer called “einfuhling,” which Damion Searls defines as “creative seeing.” As his observation about this phenomenon suggests, Burckhardt does not want to be “a really good abstract painter,” which is to say that he resists the institutionalized model regarding what constitutes an accomplished abstract painting. This resistance is what threads many of Burckhardt’s distinct bodies of work and styles together. He wants to subvert the standards of judgment integral to our understanding of abstract painting, while being committed to the act of making: he wants to inhabit his doubt and certainty without seeking a one-size-fits-all solution. He is interested in – to use his own words – perversely cultivating the tenuous relationship between “creative seeing” and the randomness of nature without becoming explicit. Can he walk that tightrope without toppling into irony or? He is also interested in following the ramifications of an idea (or something seen in his mind’s eye) to its fullest fruition, no matter how absurd the journey.

In “FULL STOP,” an empty canvas (made of cardboard, of course) sits on an easel at the center of the artist’s studio, waiting to be worked on. The studio feels abandoned and, because of that, disconcerting. Why did the artist stop?

The objects in the studio include a slide projector, dial telephone, and other obsolete objects we associate with an earlier era. Everything we see in the studio has a counterpart in reality. For all the considerable and evident effort that Burckhardt put into making this room, and the many things in it, the inexpensive materials work in counterpoint. What does it mean to make a cardboard replica of Johns’s “Painted Bronze” (1960), a sculpture of an old Savarin coffee can crammed with dirty paintbrushes, which is a hand-painted bronze recreation of an artist’s tools? By some measure, doesn’t Burckhardt return this artist’s tools to its original setting, which is a studio, however fictional it might be? Isn’t what he made both a tender homage and an absurd replica in equal measure? Isn’t it also a comment on the art market? If you cannot afford Johns’s “Painted Bronze” – which you can’t – perhaps this replica will do.

I am intrigued by Burckhardt’s interest in the appearance of a thing, and that he has not become programmatic about it. In this regard, Burckhardt shares something with Richard Artschwager and his non-functional faux furniture, not to mention his blurring of the boundaries between painting and sculpture. In his installation, “Slump” (2008), Burckhardt fabricated stretcher bars, paint cans, boxes, and crates. The fabricated paintings literally slumped against the wall: there was something funny, ironic, and – let’s face it – truly weird about these works. It is the weirdness that propelled these works into a new domain (or reality) all their own. Like Artschwager, he seems to be able to copy whatever he wants, but prefers to undermine his gift for mimicry, often by giving himself a ridiculous task: make a painting that slumps against the wall as well as the crate it is resting on, while ensuring that both look as if they are real. Like Buster Keaton, Burckhardt wants to joke about a disaster with a straight face. Which raises the question: what is real and what isn’t?

For years Burckhardt has painted on uneven cast-plastic surfaces, adding black dots to the sides to mimic the tacks used to hold a stretched canvas to its wooden support. In his last exhibition, AKA Incognito at Tibor de Nagy (May 7–June 12, 2015), which I reviewed, he showed two groups of paintings, one on cast plastic supports, the largest of which measures 32 by 40 inches, and larger works done on stretched canvas, including a two-panel painting, “Gunung” (2015), which measures 60 by 96 inches and is done on two panels. The paintings currently in his studio extend out of “Gunung.”

When I saw these two groups of paintings, one on plastic and the other on canvas, I wondered how would connect the two, the fake to the so-called real? One thing he did on the “real” paintings in his studio, all canvas on stretched linen, was to use a jigsaw on the stretchers, making the edge wavy. At times, while looking at the paintings, the wavy edge became a soft irritant: I was aware of it the way I am of a distant, buzzing bug. At the same time, it contradicted the straight and curving edges of the forms, as there was nothing wavy about them.

The edges of these new paintings invite closer scrutiny; are they composed of hardened paint extending beyond the physical edge, as in some works by Miguel Barcelo? What does it mean to contradict Donald Judd’s declaration, in his landmark essay, “Specific Objects” (1965)?

The main thing wrong with painting is that it is a rectangular plane placed flat against the wall. A rectangle is a shape itself; it is obviously the whole shape; it determines and limits the arrangement of whatever is on or inside of it.

There is no dialogue between the painting’s gently wavy edges and the interior forms. They are two different languages spelled out simultaneously.

In the new paintings – none of which have been titled yet – Burckhardt uses brushes, rollers, and a drywall knife to scrape the surface. He also uses a Mylar sheet with hand-cut holes in tandem with a brush or roller to make rows of dots that hover between the handmade and machine-made. The palette for each painting is different. The combination is never charming or seductive. The paint varies from solid to porous.

A number of visitors to Burckhardt’s studio, after seeing these paintings, have mentioned Pacific Northwest art and the American science fiction film, Transformers (2007), and the toys it was based on as possible inspirations, but this seems too reductive. Besides, I also saw forms that evoked the time Burckhardt has spent in India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. He has looked at a lot of stuff and has never been hierarchical about it.

My sense is that these paintings court a figural reading but never slide comfortably into that perceptual category. Are we looking at the abstracted image of a mechanical figure, or an imperfect, symmetrical abstract painting? By courting a legibility that is rooted in Pop culture, while, at the same time, resisting it, Burckhardt asks, how and what do we see? And why? What is it that we want from abstract painting?

By finding ways to foreground his conflicts about painting, while also expanding its definition, Burckhardt has become one of the most interesting artists of his generation.